Birds (2)

NEOGNATHAE

1. Introduction

The clade Neornithes includes all extant birds. The earliest divergence is between Paleoagnathae (ratites and tinamous) and Neognathae which includes the two primary taxa Galloanserae and Noeaves.

Classifications of birds following the traditional sequence of orders beginning, approximately with Struthiformes (ratites), Procelleriformes (albatrosses, petrels), Sphensciformes (penguins), and Gaviiformes (loons), and ending with Piciformes (woodpeckers) and Passeriformes (perching birds), as found in most field guides and checklists (e.g. Peters 1931 - 1951), are weakly connected to phylogenetic hypotheses, and tell us as much about the history of ornithology as about the history of birds. A recent and revised classification of modern birds (Sibley and Monroe, 1990) reflects phylogenetic hypotheses, with sister groups being assigned coordinate ranks (following Hennig, 1966).

"Land Birds" and "Water Birds" are informal names for two large clades within Neoaves, each encompassing several traditional orders.

This account of classification of classification is taken from the tolweb.org pages, which continue as follows:

"Land Birds" is an informal name for a large and diversed group supported only by molecular characters (Hackett et al. 2008, Ericson et al. 2006. It encompasses most -- though by no means all -- of the familiar group of land birds, including the largest order, Passeriformes, which comprises over half of all bird species.

Two traditional orders, Falconiformes and Coraciiformes have been split. The family Falconidae (falcons) is not a close relative of the remaining falconiformes, and thus Falconiformes is limirted to a single family(the falcons). The remaining birds of prey traditionally included within Falconiformes have been given their own order Accipitriformes.

References.

Of the groups not listed above, mention must be made of the following:

CUCULIFORMES (Cuckoos) | COLUMBIFORMES (Pigeons) | PHOENICOPTERIFORMES (Flamingos)

Classification. The classification of "Land Birds" is as follows:

| | | - | Passeriformes (Perching Birds) | |||||||||

| | | - | | | |||||||||

| | | | | - | Psittaciformes (Parrots) | ||||||||

| | | | | ||||||||||

| | | | | Falconiformes (Falcons) | |||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| | | Cariamidae (Seriemas) | ||||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| | | | | - | Coraciiformes (Kingfishers and relatives) | ||||||||

| | | | | - | | | ||||||||

| | | | | | | - | Piciformes (Woodpeckers and relatives) | |||||||

| LAND BIRDS -- | | | | | - | | | |||||||

| | | | | | | Bucerotiformes | (Hotnbills and Hoopoes)||||||||

| | | | | - | | | ||||||||

| | | | | | | Trogoniformes (Trogons) | ||||||||

| | | - | | | |||||||||

| | | | | Leptosomatidae (Cuckoo Roller) | |||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| | | Accipitriformes (Hawks, Eagles, Vultures and relatives) | ||||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| | | Strigiformes (Owls) | ||||||||||

| | | |||||||||||

| | | Coliiformes (Mousebirds, Colies) | ||||||||||

Links

2. Water Birds

The classification of 'Water Birds' is as follows:

| | | - | Procelleriiformes (Tube-nosed Seabirds) | |||||

| | | - | | | |||||

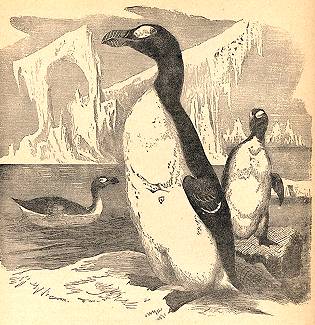

| | | | | - | Sphenisciformes (Penguins) | ||||

| | | - | | | |||||

| | | | | | | - | Ciconiiformes (Storks) | |||

| WATER BIRDS -- | | | | | - | | | |||

| | | | | - | Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Cormorants, Herons and relatives) | ||||

| | | |||||||

| | | Gaviiformes (Loons) | ||||||

The clade Sphenisicoformes consists of Penguins, which are the best known of all life forms in Antarctica. An interesting page on Antarctic Penguins is found at the site www.rosssea.info. This site also has information on more general forms of Sub-Antarctic and Polar bird life including the Albatross. Albatrosses have a special place in maritime lore and superstition, most memorably evoked in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. This poem, published in 1798, begins with the introduction:

| ARGUMENT How a ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropicsl Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; how the Ancient Mariner cruelly and in contempt of the laws of hospitality killed a Sea-bird and how he was followed by many and strange Judgements: and in what manner he came back to his own country |

James Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle several times during 1772 - 1774, reaching 71oS on 30 Jan 1774. James Clark Ross's expedition reaching 78o4'S was in 1839, 41 years after the poem.

A large number of water birds live in the Southern Hemisphere, close to the Antarctic.

Albatrosses belong to the clade Procellariiformes, which consists of four families:

Procellariidae | Diomedeidae | Hydrobatidae | Pelecanoididae

The oldest known penguin is the Waimanu. The rocks containing the Waimanu manneringi skeleton are 61.6 million years old, and a close relative, the smaller Waimanu tuatahi 58 - 60 million years old.

Source: Molecular Biology and Evolution 23(6): 1144 - 1155

Kerryn E. Slack et al.: Early Penguin Fossils, Plus Mitochondrial Genomes, Calibrate Avian Evolution

The Vegavis, mentioned in the figure above, is the oldest known member of the clade galloanserae. We see that both Waimanu and Vegavis evolved before the K-T boundary.

3. Bird Extinction

At least132 bird species have become extinct since the year 1500. Furthermore at least 1244 of the 9856 living bird species are threatened with extinction. More information and a list of extinct birds is found at

http://extinct.petermaas.nl/extinct/lists/birds.htm

Notable among the birds listed here are

3.1 Haast's Eagle.

Family: ACCIPITRIDAE

Species: Harpagornis moorei

Dr. Julius von Haast described two species of eagle, one on the basis of small birds which are now believed to represent the male. Harpagonis asimilis Haast, 1874. The Maori seemed to have called the bird Te Pouakai or Te Hokiri. they were also depicted in rock drawings.

Haast's Eagle had a weight of approximately 10 - 13 kg and a wingspan of up to 2.6 m for a large female. According to a Maori myth it made the cry "Hokiri-hokiri". The eagle attacked a variety of flightless birds found in New Zealand including the now extinct Moas,

This eagle was found all over the South Island during the Pleistocene, but mostly restricted to the south and east after the Ice Age. The arrival of people in new Zealand had unfortunate consequences for the bird's forest habitat. It was likely extinct by 1400 AD.

3.2 Dodo

Order: COLUMBIFORMES

Species: Raphus cucullatus

This was a flightless bird about 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) which weighed up to 20 kg. It was found in Mauritius. It had large legs, short little wings, a short nect and a 23 cm long thick bowed beak. The sailors who landed in Mauritius found much amusement in watching the clumsy dodo's behaviour. The extinction of the dodo is commonly dated to the last sighting in 1662. The birds were killed by thousands for food not only by humans, but by pigs, rats, dogs and cats.

Both were Ratites (flightless palaeognathae).

The ELEPHANT BIRD (Aepyornis maximus) inhabited the island of Madagascar. Legends of the giant roc (rukh) were probably based on it. In Chapter 33 of his memoirs, "Concerning the Island of Madagascar" Marco Polo wrote that the Great Khan had sent him to investigate curious reports of giant birds.

The Malagasy people were in contact with the Arabs for several centuries, but fiercely resisted colonisation. The first Europeans to visit the island were the Portuguese in 1500. In the 16th century, Dutch, Portuguese and French sailors returned from the Indian with huge eggs taken as curios. The bird was probably extinct in 1649. The first French Governor of Madagascar and Director of the French East India Company, Étienne de Flacourt, wrote, in 1658, "vouropatra -- a large bird which haunts the Ampatres and lays eggs like the ostriches; so that the people of these places may not take it, it seeks the most lonely places." By 1700, it was gone for ever.

The elephant bird was the largest bird ever to have lived. They resembled heavily built ostriches, with small heads, vestigial wings and long, powerful legs. They stood 10 ft (3 meters) tall and weighed approximately 1000 lbs(455 kg). Their eggs had a circumference of about 3 ft (91 cm), were about 13 inches (33 cm) long and had a capacity of 2 imperial gallons (9 liters). They existed for 60 million years (much longer than humans).

The New Zealand GIANT MOA (Dinornis giganteus) was more lightly built than the elephant bird, but still had three times the weight of a large man at up to 200 - 275 kg. Some were taller than the elephant bird at 13 ft (4 meters) to the head. The Giant Moa eggs measured 10 inches (24 cm) long and 7 inches (18 cm) wide. Females were 1.5 times the size and almost three times the weight of males.

When the first Polynesians arrived in New Zealand around the 10th century, becoming the Maori, the dominant life forms were these giant birds that lived in the fringes of the semi-tropical forests and on the grasslands which the Maoris called the 'Moas'. The Maoris made legends of the giant moa, calling it the Poua-Kai.

By the time the Europeans discovered the islands in 1770, the giant moa had been hunted to extinction; their official extinction date is given as 1773.. With only one natural predator large enough to tackle them (Haast's eagle) they were the dominant terrestrial species on the islands. One striking feature of moa anatomy is the complete lack of humeri (upper arm bones). This means that they had no trace of even vestigial wings.

The following is taken from the entry for Moa in Harmsworth Natural History (1910):

The fate impending in the case of kiwis has long since overtaken their gigantic extinct cousins the moas (family Dinorthidae), which had already disappeared from New Zealand when those islands were first colonised from Europe, although there is good reason to believe that they lived on till the last five hundred or four hundred years, if not to a considerably later date. These birds, of which not only the bones, but in some cases the dried skin, feathers, and egg-shells, as well as the pebbles they were in the habit of swallowing, have been preserved in the superficial deposits of New Zealand, attained a wonderful development in those islands, where they were secure from persecution till man appeared on the scene. Not only did the larger members of the group far exceed the ostrich in size, but they were extraordinarily numerous in species, as they were also in individuals; such a marvellous exuberance of gigantic bird-life being unknown elsewhere on the face of the globe in such a small area. As regards size, the largest moas could have been but a little short of 12 feet in height, the tibia being considerably over a yard in length; while the small were not larger than a turkey. in reference to their numbers, it may be mentioned that there are some twenty species, arranged in about six genera; and the surface of many parts of the country, as well as bogs and swamps, literally swarmed with their bones. Some of the moas had four toes to the foot, and others three, but all differed from kiwis in having a bony ridge over the groove for the exterior tendons of the tibia. They are, therefore, evidently the least specialised of the members of the order yet mentioned, seeing that this bridge is present in the majority of flying birds, and has evidently been lost in all the existing Ratitae. While agreeing in some parts of their organisation with kiwis, moas are distinguished b the short beak and the presence of after-shafts to the feathers while in the larger forms, at any rate, not only the wing, but likewise the whole shoulder-girdle, wanting. There is, however, reason to believe that certain pygmy moas -- which from their size were the most generalised members of the group -- retained some of the bones connected with the wing. Moas were represented by several very distinct structural modifications; the largest being the long-legged, or true, moas (Dinornis) characterised by the long and comparatively slender leg-bones, and also the large and depressed skulls. In marked contrast to these were the short-legged, or elephant-footed, moas (Pachyornis), in which the limb-bones are remarkable for their short and massive form; the metatarsus being most especially noteworthy in this respect. In these birds the skull is vaulted and the beak narrow and sharp; but in the somewhat smalller and less stoutly-limbed-broad-billed moas (Emeus) it is broad, blunted, and rounded. The other species, in all of which the beak was sharp and narrow, are of relatively small stature, and include the smallest representatives of the family, some of which were less than a yard in height. The eggs of the moas were of a pale green colour, and probably formed a favourite food of the Maori, by whom these birds were evidently exterminated.

3.4 Passenger Pigeon.

Order COLUMBIFORMES

Species: Ectopistes migratorius

This was probably once the most numerous bird species on the planet, living in North America, east of the Rocky Mountains. It was similar to but larger than the mourning dove. The immense roosting and nesting invited over-hunting.

This bird had a slate blue head and rump, slate grey back, and a wine red breast. The colours of the male were brighter than those of the female. The eye was scarlet.

The last Passenger Pigeon, named Martha, died alone at the Cinncinati Zoo on 1 Sep 1914.

4. Bird Migration

Reference: Common Birds: Salim Ali Laeeq Futehally

The migration of birds is one of the strangest of all ornithological phenomena. Twice a year, in spring and aurumn, millions of birds take to the ari and set out on long journeys in order to get to a definite goal, sometimes across oceans and continents.

In the northern hemisphere, the autumn migration form the breeding grounds moves from north to south and from the higher altitudes to the lower. In the southern hemisphere, the directions are reversed.

While for most birds migration is a simple trip to their breeding grounds and back, even when thy choose to return by a different route, there are some adventurous individuals which make a much more complicated journey. They go to their breeding grounds. and after finishing the business of raising a family, they go on to another place as if for a holiday. Bird migration ,then is an extremely complicated intricate series of movements, some of them incomprehensible.

Experiments suggest that it is the timing of the rising and setting sun which gives migrants their final cue for departure. The sun is also their compass on their long journeys, for it is now believed that the birds take their orientation from the angle of the sun. Fogs and mists which obscure the sun can throw the off their course for a while although with the return of visibility they are able to re-align themselves fairly well. Landmarks, where they exist, are not ignored but the real guide is the sun by day and the stars by night. It has also been shown that birds are sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field. Presently, this is believed to be due what is termed the RADICAL PAIR MECHANISM in chemical reactions (PNAS vol. 106(2), Jan 2009).

A few species always travel singly, although most birds prefer to travel in large or small flocks. many small birds, otherwise diurnal, prefer to fly by night -- perhaps for greater safety from predators. The cruising speed of the smaller birds is round about 30 km. per hour, and as the wor4king day of a migrating bird is calculated to be about eight hours, one lap of the journey should be just under 250 km. Bigger birds can oftenfly steadily at 80 km.p.h. and consequently cover much longer distances in a day.

The scale of the migratory movements is difficult to imagine. It is estimated that of the species which breed in Europe and the northern part of Asia, about 40% are migrants, that is, just less than half. Of the 68 species of songbirds in Britain, 22 species are migrants, and of the 1200 species of all kinds found in India, over 300 come from distant lands in winter. In another sense, too, the scale of the journeys is astonishing. The Arctic Tern (Order: Charidriiformes, Family: Laridae, Genus: Sterna) flies from the North Pole to the South Pole and back every year -- a round trip of some 35,000 km. It is not unusual for birds to make a journey of seceral thousand kilometers: many of the species which breed in Europe go as far as S Africa for the winter; it is also true that a great number simply make a dash for the Mediterranean countries and stay there.

| Arctic Tern |

5. Charadriiformes -- Shore Birds

There are about 350 species in this order, found all over the world. They live near or on the water. There are 16 families in this order. According to tolweb, this clade is the one most closely related to land birds. (See www.biology.ufl.edu/earlybird/pubs.html#Deep_Avian_Phylogenetics for references on the subject, in particular, the paper by Hackett et al. (2008), Science 320: 1763 - 1768.)

| Alcae | Charadrii | Lari |

| Alcidae -- auks, murres | Burhinidae -- thick-knees Charadriidae -- plovers, lapwings Chionididae -- sheathbills Dromadidae -- crab plover Glareolidae -- pratincoles, coursers Haematopodidae -- oystercatchers Ibidorhynchidae -- ibisbill Jacanidae -- jacanas Pedionomidae -- plains wanderer Recurvirostridae -- avocets, stilts Rostratulidae -- painted snipe Scolopacidae -- snipe, sandpipers Thinocoridae -- seedsnipe | Laridae -- gulls, terns Rhynchopidae -- skimmers |

5.1 Plovers. As we can see, the best known Charadriiformes group is the Plover ( Family: Charadriidae, Subfamily: Charadriinae, 8 genera including Charadrius). The Oxford Dictionary defines Plover as "a wading bird with a short bill."

The book by Salim Ali and Laeeq Futehally states:

The Order CHARADRIIFORMES is a large and heterogeneous conglomeration of 13 families of water-or-waterside birds, well represented on the Indian subcontinent by resident as well as migratory forms. . . .

Of the family CHARADRIIDAE -- Plovers, Sandpipers, etc. -- many forms are resident and others visit us during winter mainly from northern lands. The Redwattled Lapwing (Vanellus indicus) -- Hindi: Titeeri or Tituri, is the commonest and most familiar of our resident plovers. it is the size of the Grey partridge, bronze-brown above, white below, with black breast, head and neck, and a crimson fleshy wattle in front of each eye. A broad white band from behind the eyes runs down the sides of the neck to meet the white underparts. pairs or small scattered parties of 3 or 4 haunt the open country, ploughed fields and grazing grounds, usually damp and preferably with a pond or puddle nearby. The spend their time running about in short spurts, picking up titbits in the typical manner of plovers, bill pointed steeply to the ground, and are quite as active and wide awake at might as during daytime. . . .

The Little Ringed Plover (Charadrius dubius) -- Hindi: Zirrea or Merwa, is slightly smaller than the quail. it is a typical plover, sandy brown above, white below, with a thick round head, bare slender legs, and a short stout pigeon-like bill. It has a white forehead and black forecrown, ear coverts, and round the eyes, and a complete black band round the neck, separating the white hind collar from the brown back

Absence of a white wing-bar in flight distinguishes it from the confusingly similar Kentish Plover (C. alexandrinus). The birds keep in pairs or small scattered flocks on damp tank margins, river banks, and tidal mudflats. They run along the ground in spurts with short quick mincing steps, stopping abruptly every now and then to pick up some titbit with the peculiar steeply tilting movement typical of plovers. They have a curious habit, when feeding on soft mud, of drumming with their toes in a rapid vibratory motion in order to dislodge insects, sandhoppers snd tiny crabs lurking in burrows and crevices. These constitute their normal food. In their normal environment, their coloration blends with the surroundings in a remarkable way, making the birds difficult to spot so long as they remain motionless. Although these little plovers are scattered while feeding, yet no sooner does one take alarm and rise than the rest promptly follow suit, all flying in a compact body at great speed, turning, twisting, and banking together, their white undersides flashing in unison from time to time. The flight, attained by rapid strokes of the pointed wings, is swift but seldom more than 4 or 5 metres above the ground. The eggs -- almost invariably 4, are laid among the shingle on dry sandbanks in a riverbed. They are of the typical peg-top shape of plover's eggs, buffish stone to greenish grey in colour with scrawls and spots of dark brown and purplish. They harmonise perfectly with their surroundings and are difficult to spot even when their position has been carefully marked down from a distance.

Another related bird mentioned in this book is the Stone Curlew or Goggle-eyed Plover (Burhinus oedicnemus -- Hindi: Karwantak or Barsari. It is a brown-streaked plover-like ground bird, larger and more leggy than the Grey Partridge, with thick round head, bare yellow 'thick-kneed' legs, and large yellow 'goggle' eyes. It belongs to the family BURHINIDAE.

5.2 Auks. These are medium-sized seabirds with long, barrel-shaped bodies, short tails, very small wings and short legs set far back on the body. Examples are:

| Black guillemot |

| Guillemot |

| Little Auk |

| Puffin |

| Razorbill |

The Little Auk (alle alle) is a small seabird, the size of a starling. it has a black stubby bill and a short neck and tail. it is a winter visitor to the waters around the UK in small numbers each year. It breeds in the Arctic and winters in the North Atlantic.

The Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis, Linnaeus, 1758), now extinct, was a 75 cm auk, the only one unable to fly due to atrophy of its wings. It resembled a penguin not only with its small wings, but also with its black back, white abdomen, and upright posture. in winter the birds underwent a plumage change similar to that experienced by their relatives the guillemot and razorbill. The black of the foreneck and chin were replaced by white, and the lozenge-shaped white patch between the eye and beak disappeared.

By the late 1600s the Great Auk population dramatically declined owing to commercial exploitation for feathers, meat and oil. By the end of the 18th century, the only remaining breeding place of this bird was the island of Geirfuglasker of south-western Iceland. In 1830, an underwater volcanic eruption and earthquake destroyed Geirfuglasker. The greater part of the remaining Great Auks perished during or after this disaster. The surviving ones settled on the nearby island of Eldey, where they were hunted to death. The last Great Auk hunt took place on 3 June 1844.

Great Auk

The fate of the Great Auk is mentioned in The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley (1862), in Chapter 7, where it is called the Gairfowl, its Icelandic name.

5.3 Terns. The family LARIDAE is composed of Gulls, Terns and Skimmers. Gulls differ from terns superficially in being rather heavier built with broader and less pointed wings. Ali and Futehally write (of species seen in India):

One of our commonest species is the Brownheaded Gull (Larus brunnicephalus) -- Hindi: Dhomra. It is slightly larger than the Jungle Crow, grey above and white below, with a dark coffee-brown head in summer. In winter, whilst with us, the head is greyish white, sometimes with a crescent-shaped vertical mark behind the ear. it may be distinguished from the equally common but somewhat Blackheaded Gull (L ridibundus) by the prominent white or 'mirror' patch near the tip of the black first primary quill; in the Blackheaded species the first wing quill is white with black edges and tip. Young birds of both species have a black bar near the tip of the white tail. Both are often found together on the seacoast; less common inland. These gulls arrive in India in September-October to spend the winter on our coasts and are mostly gone again by the end of April.

The book lists the Indian Whiskered Tern and the River Tern as found in India.

The Indian Whiskered Tern (Chlidonias hybrida) -- Hindi: Tehari, Koori (all terns), is a slender graceful silvery grey and white bird about the size of a pigeon. It belongs to the group known as 'marsh terns' characterised by a tail which is only slightly forked (almost square-cut). The bill is red or blackish red, and when at rest the tips of theclosed wings project beyond the tail. It is usually seen over marshland, inundated pady fields or coastal mudflats.

The River Tern (sterna auranta) keeps more to rivers than to marshes. It is also grey and white with a brown-speckled cap but somewhat larger, with a yellow bill, and a longer more deeply forked swallow tail.

A detailed list of tern species is found at WoRMS (1013), Sternidae. World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=148764.

Eight genera are listed:

The Arctic Tern is listed as Sterna paradisaea (Pontoppidan, 1763). This page gives the following details:

Description: Length: 33 - 41 cm. Plumage: tail, rump, back and wings pale grey, wingtips darker grey; hind neck white; forehead white, forecrown speckled white; below white; breeding bird has pearl grey below, cheeks white; deeply forked tail extends slightly beyond wing. Immature browner on back. Bare parts: iris dark brown; bill red in breeding and balck in non-breeding birds; feet and legs red in breeding and black in non-breeding. Habitat: open ocean and seashores. Palearctic migrant.

Dimensions: Length: 15 1/2" (39 cm); Wingspan: 31" (79 cm).

Reproduction: Breeds in the Arctic and Subarctic of North America and Eurasia. In America, it breeds from Greenland to Alaska, and on the Atlantic coast locally south to New England. Winters in the southern hemisphere on the waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans as they approach the Antarctic continent.

6. Land Birds

The group 'land birds' is supported only by molecular characters. The largest of all land birds is the Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) which inhabits the Andean mountains. This is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae, which is different from the falcons.

The most crowded bird order is PASSERIFORMES, which is contained in the land bird clade. This order is defined in the page Passerine Definition at birding.about.com. The page states that:

The most prominent characteristic of passerine birds is the anisodactyl arrangement of toes. These birds have four toes, three facing forward and one backward, which allows the bird to easily cling to both horizontal and nearly vertical perches, including branches and tree trunks. These birds also have an adaptation in their legs that gives them extra strength for perching, and in fact, the relaxed position of their feet and talons is to be clenched securely, so the birds are able to perch easily even sleeping.

6.1 Falconiformes.Falcons are closer to the passerines than are the accipitridae. Trained falcons have been used traditionally to hunt wild quarry; this practice is known as falconry. Evidence suggests that falconry may have begun in Mesopotamia, possibly as early as 2000 BC. It was probably introduced to Europe around AD 400, when the Huns and Alans invaded from the East. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194 - 1250) is generally acknowledged as the most significant wellspring of traditional falconry knowledge. Most falcon species used in falconry are specialised predators, most adapted to capturing bird prey such as the Peregrine Falcon (falco peregrinus)and Merlin (falco columbarius). A list of books on falconry is found at North American Falconers Association.

| BIRDS OF PREY These are also known as raptors. They are carnivorous birds with strong bills, large talons and exceptional flight capabilities. They include the families Accipitridae and Falconidae, also Owls and Shrikes. | |

ANDEAN CONDOR Vultur gryphus Order: Disputed. Classified as Accipitriformes by tolweb Sub-order: CATHARTIAE Family: CATHARTIDAE Genus: VULTUR (New World Vultures) |

PEREGRINE FALCON Falco peregrinus Order: FALCONIFORMES Family: FALCONIDAE Genus: FALCO |

| The Andean Condor is the largest of all land birds. See animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Vultur_gryphus/pictures for more information. | The Peregrine Falcon was seriously endangered by DDT Spraying in the 1960s. See Malaria and DDT at this site. This is part of the subject matter of Rachel Carson's book The Silent Spring, and led to the banning of DDT in the USA in 1973. |

6.2 Psittaciformes. This is the land bird clade most closely related to passeriformes. it is a group of birds that includes lorikeets, cockatiels, cockatoos, parakeets, budgerigers, macaws, broad-tailed parrots and others. See animals.about.com - Parrots for more information.

Parrots have large heads, curved bills, short necks and narrow, pointed wings. They occur mainly in tropical and subtropical regions. They are intelligent birds and are capable of imitating a variety of sounds including the human voice.

There are three groups of parrots, the cockatoos (Cacatuidae), true parrots (Psittacidae), and New Zealand parrots (Strigopidae).

The FoxP2 gene, which is linked to human speech, is also found in parrots. see Journal of Neuroscience 31 March 2004 24(13), 3164-3175.

With the exception of the Kea (Nestor notabilis), a new Zealand parrot which occasionally eats other bird's chicks and lizards, and is also known to attack sheep, parrots feed almost exclusively on fruit, seeds, nuts and nectar. Some species occasionaly feed on arthropods.

6.3 Passeriformes. These will be discussed in detail on the next page.

Completed 02 Oct 13